‘Eighteenth-Century Female Readers in @NT_Libraries’: this paper analyses the in-situ book collections @tatton_park , @NTLymePark and Townend for evidence of female ownership, book-use and book circulation. @ResearchNT #EMQuon 1/14

Surviving libraries hold a fraction of the material originally at the property. #18thcentury books were likely moved between properties. Collections have also been subject to book sales. #EMQuon 2/14

The libraries we visit today are a set-dressing, they provide a snapshot into the library at a moment in its history. It’s difficult to distinguish between books part of the original book collection and those which have since been put into the library by curators. #EMQuon 3/14

While we know from women’s correspondence, diaries and account books that they read widely, this is often not reflected in private library collections. Biographical details about these women are scarce and require searching through archival traces. #EMQuon 4/14

Textual markings can be broadly split into 3 sections: ownership signatures, marks of recording (acquisition) and ‘active’ signs of reading (e.g. notes in the margins). #EMQuon 5/14

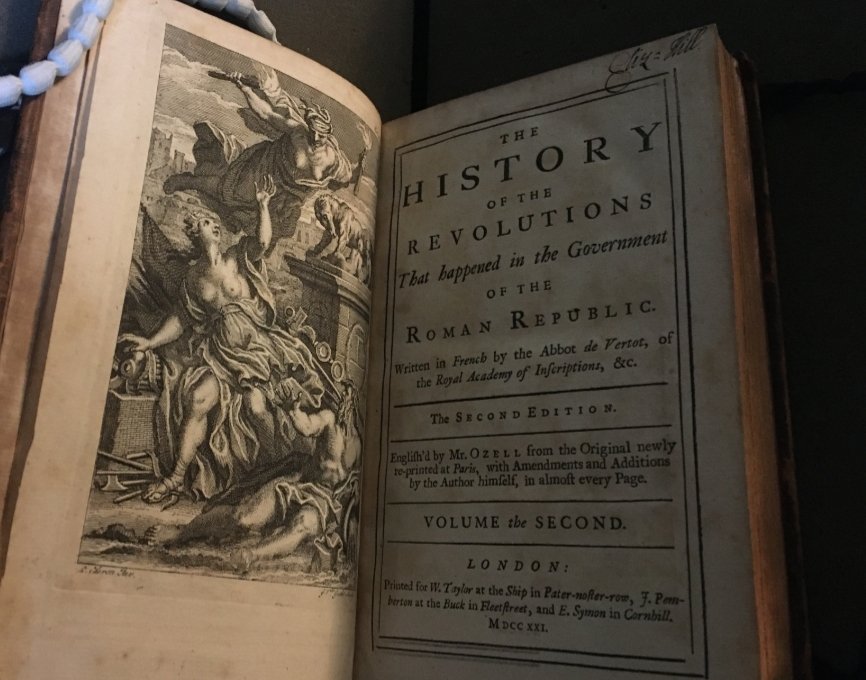

Ownership marks are the most common form of annotation and signal a book as a physical object to be catalogued and valued. Books such as ‘The History of the Revolutions’ @tatton_park (pictured) contain sigs such as Eliz Hill (d.1727) but no other signs of reading. #EMQuon 6/14

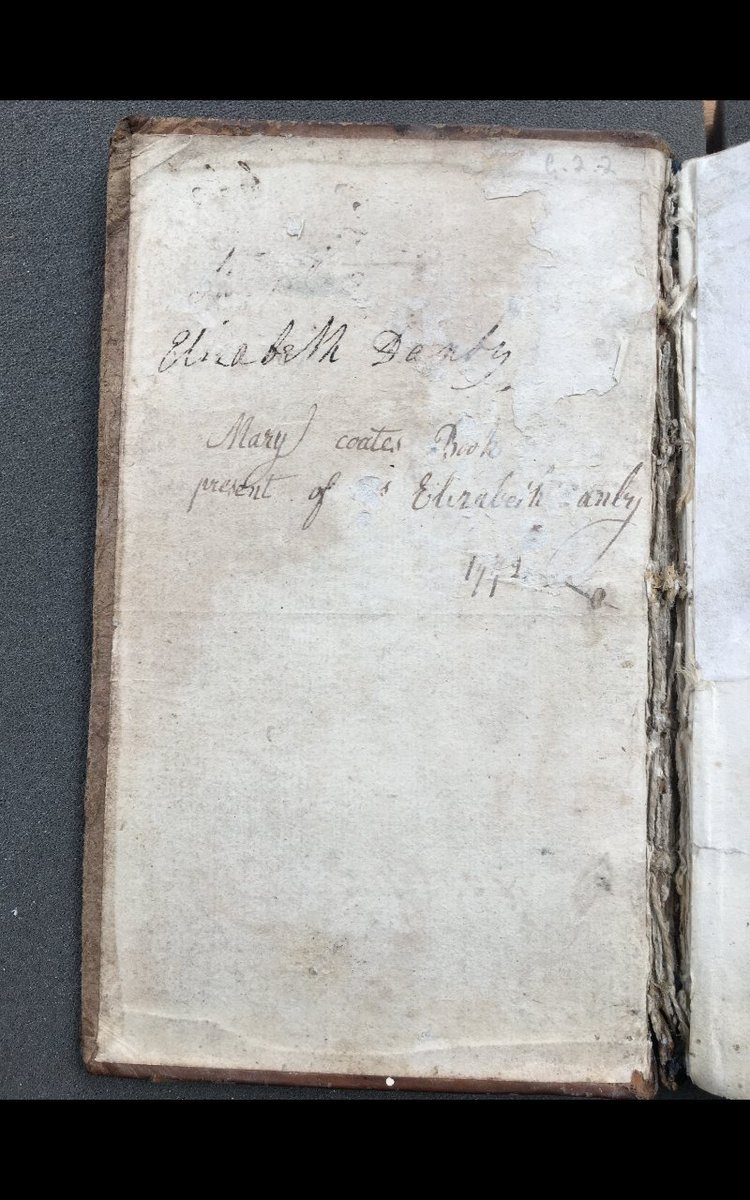

Marks of recording supplement ownership sigs and detail book acquisition. Manuscript inscriptions in a 1765 copy of Clarissa at Townend detail the date the book was gifted to Elizabeth Danby. Book gifting was common throughout the period. #EMQuon 7/14

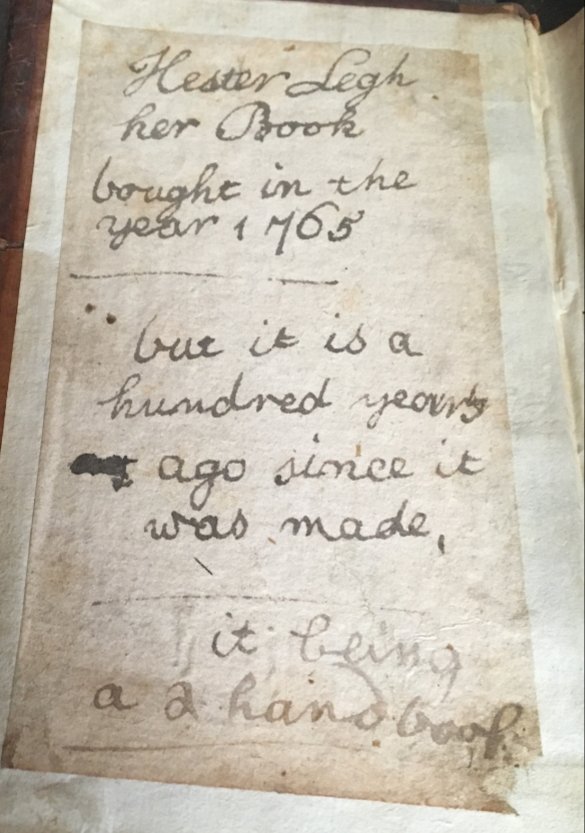

In another example, Hester Legh (d. 1789), third daughter of Peter VIII (1708-92) @NTLymePark details the date (1765), the condition (2nd hand) and the original publication date of her copy of Samuel Butler’s Hudibras. #EMQuon 8/14

Finally, active reading suggests that a book has been engaged with and re-read. Though many examples exist of marginalia, it is important to acknowledge that far more books exist with no marks. However, marginalia can offer insights about how books were read. #EMQuon 9/14

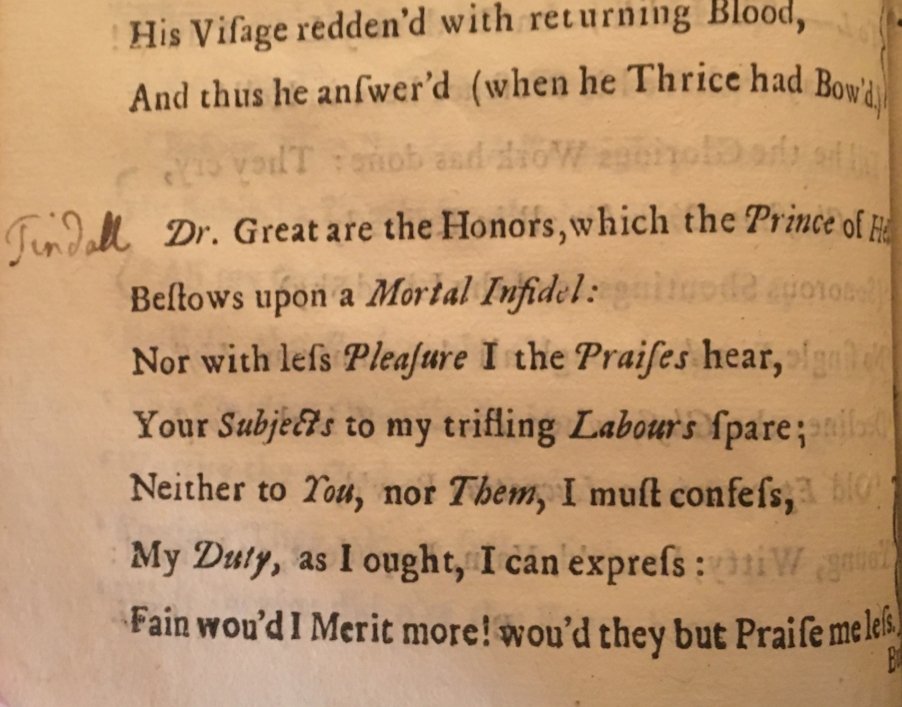

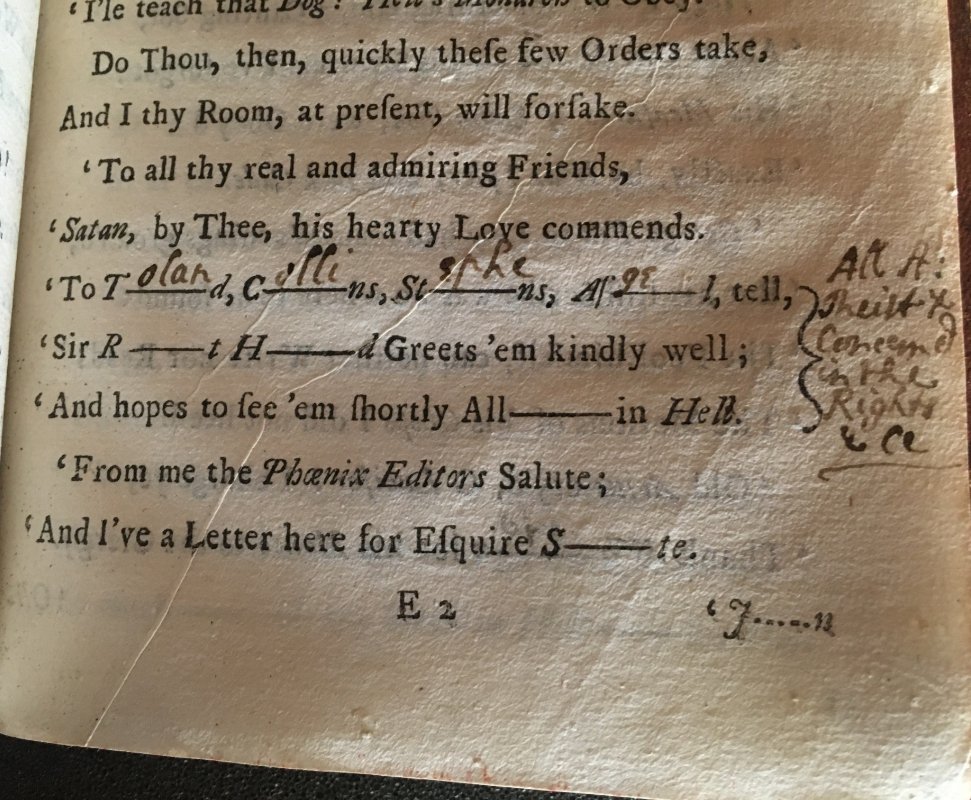

Frances Legh’s copy of Abel Evans poem @NTLymePark contains gaps which invite the reader to annotate their copy. Legh writes the name of the doctor, Tindall, and fills in gaps within the poem. This is a type of directed annotation invited by the text. #EMQuon 10/14

Readers frequently added information to their books, either copying author’s notes or writing in the margins. Elizabeth Wilson’s copy of Constantine the Great at Townend contains her sig and additions to the list of characters which supplement the printed list. #EMQuon 11/14

Using the book collections at the National Trust, this paper has illustrated the different ways women marked their books. Ownership sigs, marks of recording and comments in the margins of the books all attest to reading experiences. #EMQuon 12/14

My research demonstrates the need to pay greater attention to female reading experiences within private libraries. Once archives re-open, I will begin to explore the archival traces women left of their reading, utilising a similar methodology to @_katie_crowther #EMQuon 13/14

Archival research will supplement my current bank of evidence and allow me to make further comparisons about shared reading experiences across northern National Trust properties.

Thank you for reading along! #bookhistory #18thcentury #EMQuon 14/14

Thank you for reading along! #bookhistory #18thcentury #EMQuon 14/14

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter