Evidence suggesting newborn babies could copy adults led scientists to believe that our ability to imitate must be innate. In fact, studies on neonatal imitation are a cautionary tale that bold claims in science need careful tests. A thread

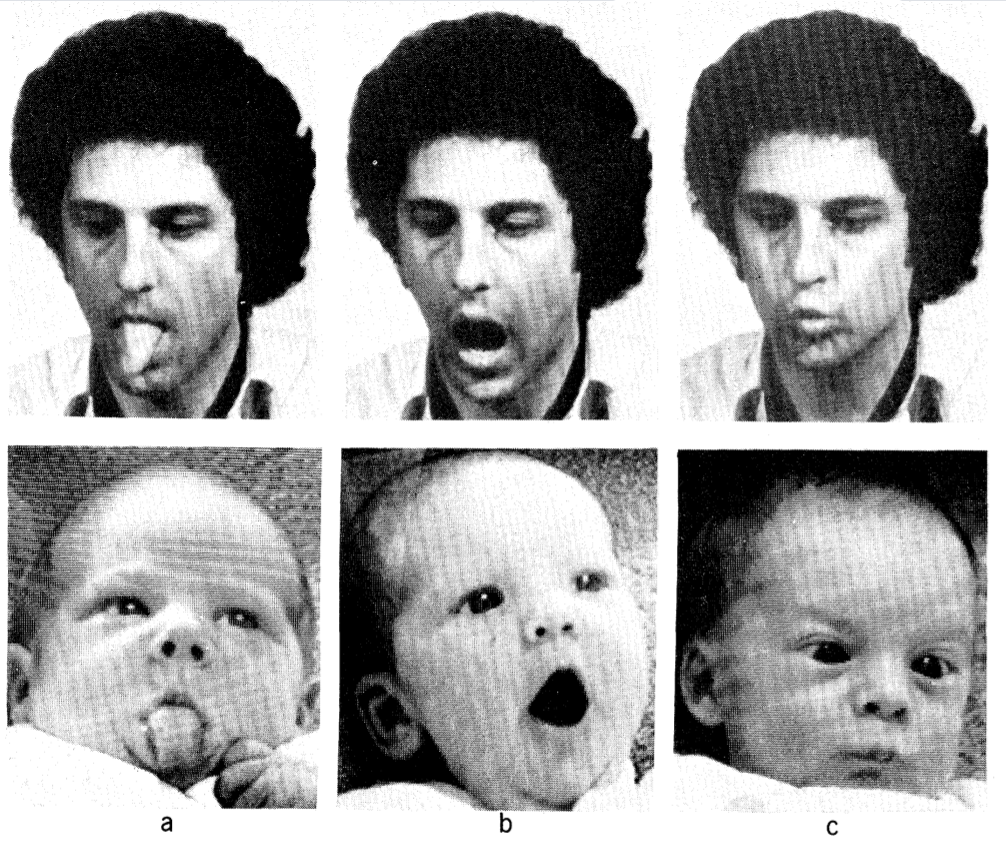

In a now-famous study, Meltzoff and Moore found that when adults protruded their tongues or opened their mouth to a group of newborn babies (2-3 weeks old), the babies were more likely to produce the same actions back.

This was exciting as - despite appearences - this facial imitation is a rather sophisticated cognitive achievement, translating seen but unfelt actions from another into felt but unseen motor programs of your own face.

Crucially, babies this young don't have much (if any) experience of seeing their own faces move. So if neonatal imitation exists it may suggest mirror mechanisms are innate (going against the idea that these ideas are forged through learning) https://twitter.com/iamscicomm/status/1291317549829885952?s=20

However, there's an important problem with how these experiments are interpreted. In particular, if you look closely across the studies it seems that babies only actually imitate one gesture - *tongue protrusion*. Why would that be? https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1467-7687.2010.00961.x

Susan Jones found newborn babies stick their tongues out when presented with a range of interesting things like flashing lights or bursts of music. So maybe infants aren't copying you when you stick your tongue out - it's just interesting? https://srcd.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1467-8624.1996.tb01837.x

The debate around whether neonatal 'imitation' is truly imitative raged on for years. That was until an elegant study led by Janine Oostenbroek comprehensively investigated whether babies really can copy. https://www.cell.com/current-biology/fulltext/S0960-9822(16)30257-3

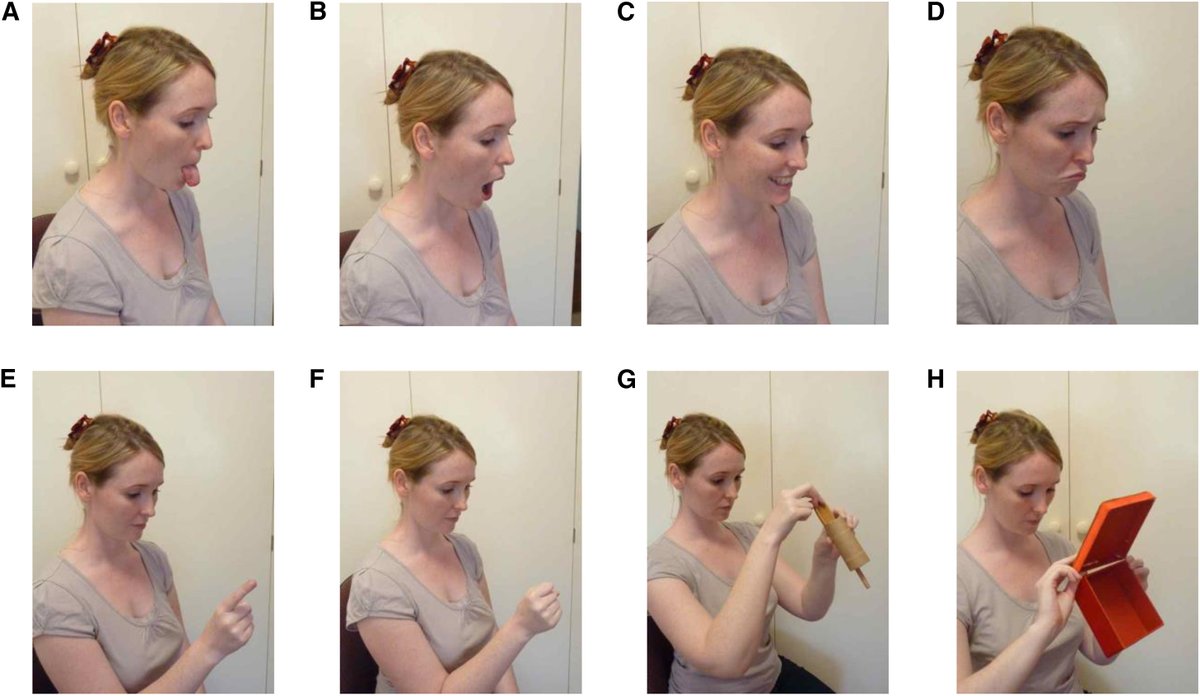

Oostenbroek & co tested a much wider array of actions than any previous study, and tracked behaviour in infants over the first 9 weeks of life.

While this study replicated the original M & M finding (that infants would stick out their tongues more when they saw an adult's tongue), across the board there was no evidence of imitation (i.e. the matching red lines were not consistently above the mismatching black ones)

This study gives us strong cause to doubt that newborns can imitate, and challenges the idea that imitation is 'in our genes'. If you'd like to learn more about the study and it's context you can read this piece by me & @RichCook111 https://theconversation.com/the-imitation-game-can-newborn-babies-mimic-their-parents-61732

The story of neonatal imitation is a cautionary tale for cognitive science. It was not that these findings weren't reliable - newborn infants really do poke their tongues back at you! Rather, one piece of data is compatible with many possibilities ways the mind might work.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter