Loving every bit of this: Metascience as a scientific social movement, by David Peterson and @AaronPanofsky https://osf.io/preprints/socarxiv/4dsqa/

"[R]egardless of whether one believes there is a legitimate crisis of reproducibility or not,it must be acknowledged that the crisis narrative added significant tailwinds to metascience both intellectually and financially." (p.11)

"The warrant for metascience is largely founded in the replication crisis." (p.16)

"This metascientific philosophy of science, in which scientists are in the business of producing, curating, and maintaining data differs markedly from philosophies of science which revolve around the theory or the exp. system. It is a post-human theory of science [...]" (p.20)

"[T]he project itself seems to be founded on a set of ideas that find few supporters in the philosophy or social studies of science: that “science” is a coherent entity on which to intervene, that there is a singular method for science, 1/2

that “efficiency” is a meaningful concept in the area of basic research. [Which] seem[s] to be at odds with one of the central findings of science studies, that “science is not one, indivisible, and unified, but that the sciences are many, diverse, and disunified.”" 2/2 (p. 21)

"Metascience is only rational in a world where science can be unified by “universal policies and procedures” and, thus, where it makes sense to think about science as a unitary object." (p. 22)

And the final sentence: "Metascience has been a frantically productive empirical field devoid of theory. A final question: how much longer can that last?" (p. 27).

And now, a recap in my own words, with some additional sprinkles.

This critique calls out metascience not for its ambition - there is nothing wrong with trying to improve science - but for the way the goal is operationalised and what the operationalisation does to science.

The unity of science is being pursued ever since it was lost (if it ever existed). Yet metascience seems to suggest that the unity of science is, in quite a few ways, unproblematic.

The “universal policies and procedures” Peterson and Panovsky refer to can be achievable, 'doable' (they cite Fujimura) under specific conditions. One of these conditions is that one ignores reality. While that sounds radical, let me explain that a bit better.

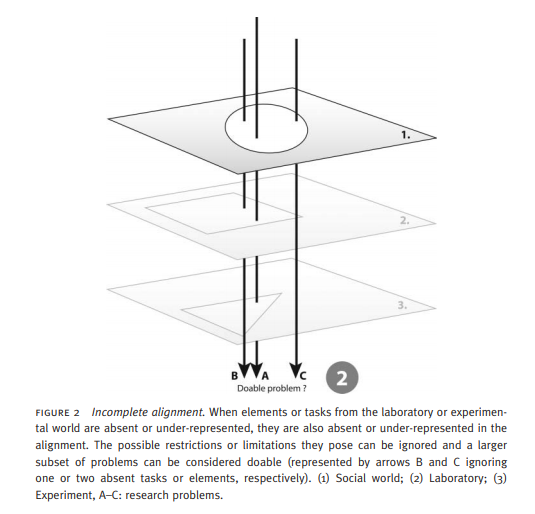

Doable problem construction is about aligning various levels of social worlds into alignment. Problems can seem doable under conditions of incomplete alignment when certain levels are insufficiently represented in the alignment. Source of the figure: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1179/030801809X12529269201200

In other words: from afar, with little eye for situated realities and key differences between disciplines, field, labs, experiments and more, 'doable' is easier than from 'the trenches' (a term also used in the paper by Peterson and Panovsky).

This is where the critique in epistemic pluralism comes in, supported by @zerdeve @IrisVanRooij @jbrittholbrook @sarahderijcke @SabinaLeonelli and so many others.

The last sentence of the paper is not a threat. Above all else it seems to suggest that at some point, key abstract metascientifc messages lose power - but concrete messages cannot ignore the pluralism in the trenches.

In the end we are stuck with the realisation that improving science is not a meta-project, not the responsibility of a few moral crusaders, not the solution to all problems.

We are left with work, labour, for all of us. We are and always have been (or at least should have been) metascientists.

Sidenote 1: That makes Peterson and Panovsky and quite a few of us, meta²scientists, studying the study of science.

Sidenote 2: That makes this thread a very tiny and shabby attempt at meta³science, studying the study of the study of science.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter