I wrote here about a misconception people have about float-weighted funds, namely that they "distort the market" by mechanically buying the stocks that rise the most, which is NOT TRUE, but I think there *is* something interesting to say https://twitter.com/macrocephalopod/status/1359988450720628736?s=20

Approx one million people wrote me to say that it's not about the funds re-weighting, it's about the FLOWS i.e. when the price of a stock goes up, the fund buys a larger $ amount of it the next time it receives an inflow. This sounds convincing but is also wrong ...

for the simple reason that if a float-weighted fund needs to buy e.g. 0.1% of the market due to a new flow, it simply buys 0.1% of the shares of every company. If you want to claim that this distorts prices you need a theory for why buying 0.1% of a companies shares causes more

price impact after it has gone up in price than it would if the price hadn't moved. There *could* be interesting theories here e.g. maybe stocks that reently went up a lot have higher beta, or lower trading volume, or worse liquidity, but no one points to that, they just repeat

the same point that the *dollar* volume of buying is larger as if saying it louder will make it more true (hint: if dollar volume is what matters then why doesn't Apple see a massive price impact every time SPY gets a new inflow?)

So it's not mechanical buying and it's not flows. What do I want to say then? Essentially that a high passive ownership of a stock *lowers the threshold* for market structure breakdowns which can cause large price swings in individual names, e.g. what happened to $GME

I can build a simple dumb model for this. Say that a stock has F shares in its float and there are S shares being shorted, which means that there are F+S shares held long. Assume that p% of the free float is held my passive vehicles who, to a first approximation, will never sell.

That means there are (1-p)F+S possible sellers. Now assume some fraction d of the possible sellers have diamond hands and will also never sell. How large does d need to be before a really epic short squeeze becomes possible?

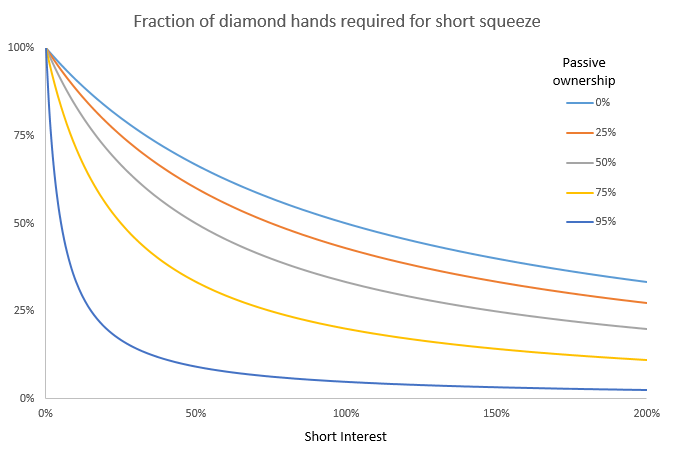

Roughly this would happen when there are more shares sold short than willing sellers i.e. when S > (1-d)[(1-p)F+S] which rearranges to d > (1-p)/(1-p+S/F)

Chart below shows d as a function of the short interest S/F for various value of p -- for low passive ownership (0-25%) you need coordination among an unreasonably high number of people for a short squeeze to occur, but as passive ownership hits 50% or 75% or 90% the fraction of

longs who need to coordinate to never sell becomes surprisingly small, especially for highly shorted stocks - something like this happened with $GME where even though there were willing sellers (e.g. Fidelity who was one of the biggest holders and sold virtually everything)

a relatively small (25%?) but committed proportion of longs who agreed to not sell was sufficient to squeeze the price to stupid levels, at least until sufficiently many shorts had been covered.

I don't think there's anything revelatory here but the basic point is that although passive investing itself is not inherently destabilizing, it can *create the conditions* for instability when other conditions are satisfied. Fin.

I will continue tagging @RobinWigg in my threads on passive investing until he follows me. Also I think the simple dumb model at the end is what @profplum99 talks about a lot but I might be wrong, he puts out a lot of material and I haven't read/watched it all.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter